Don’t get seduced by flies in urinals – a collection of cautionary nudge tales.

Author: Andrew Drummond https://www.linkedin.com/in/andrew-drummond-395336149/

We’re only human.

We’re creatures of habit.

We see what we want to see.

The idea that we’re imperfect, that we make decisions based on rules of thumb, that we post-rationalise and have (often reality-warping) preferences for the status-quo and the choices we’ve already made – these are all ideas that are deeply embedded in the way we talk about and understand ourselves. It predates behavioural science. It predates social marketing. It predates nudging. And while it’s important and exciting to acknowledge and define what we all, in many ways, already know about ourselves – and, in much the same way that observational comedy is such a joy, there really is something very satisfying about articulating a previously unarticulated shared condition - it’s equally important to understand when and how to utilise, leverage, and put our discoveries into action… and not allow ourselves to get seduced by the novelty of flies in urinals.

And there is something very alluring about the fly in the urinal.

That something as simple, cost effective, and seemingly irrelevant as etching a fly into a urinal could reduce the necessity to mop the bathroom floors so frequently, is unexpectedly exciting.

And in many cases nudging is effective, and it does work. Lollipops and flip-flops, for example:

The drinking culture in the UK often takes its toll on the emergency services. To save unnecessary expense, and to protect the well-being of citizens, police have started to give away flip-flops and lollipops.

Without interfering in the autonomy of the public, police have nudged women to take off their precarious high heels – a welcome relief for everyone involved. And lollipops have a pacifying effect, preventing potential verbal altercations from occurring. Accidents and incidents are prevented, and simultaneously the relationship between the police and the public is strengthened. A mutually beneficial, simple, effective nudge.

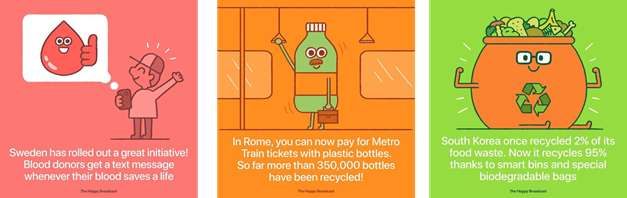

And many of the best good-news stories from 2019 owe their success to nudges.

The reality is, however, nudges may not be the solution to your problem.

Take for instance the PlayPump. It introduced the idea that the energy of ‘play’ could be utilised to pump water. Though receiving heavy publicity and funding when it was first introduced, it has since been criticised for being too expensive, complex to maintain and repair, reliant on child labour, and ultimately ineffective.

Take for instance the PlayPump. It introduced the idea that the energy of ‘play’ could be utilised to pump water. Though receiving heavy publicity and funding when it was first introduced, it has since been criticised for being too expensive, complex to maintain and repair, reliant on child labour, and ultimately ineffective.

In Hamburg, there was an issue with public urination. To rid the streets of these unpleasant and unwanted sights and smells, frequently peed-on walls were coated with  waterproof paint and signs saying “We pee back.”

waterproof paint and signs saying “We pee back.”

While it’s true that people didn’t want splash-back on their trousers and shoes, it’s also true that they still had to pee somewhere – and without public toilets to facilitate this need, there was nowhere for them to be nudged to. Apart from perhaps somewhere even less discrete.

Although not the ideal solution, harder forms of paternalism are often a necessary solution.

Hard paternalism isn't always the answer either though.

A daycare introduced fines to dissuade parents from picking their children up late. Instead of collecting their children earlier, however, parents started leaving their children later. What was intended as a punishment underwent some reframing and hedonic editing with the parents, and became a justifiable price to pay for the service of longer daycare. And when the fines were withdrawn, the problem remained. The same service was there, but it was now free!

A new scheme in Estonia, however, connects the currency that motivates the behaviour to the punishment, making motorists who break the speed limit by 20km/hr wait 45mins in a car park next to the road, and an hour if caught speeding in excess of 21km/hr.

This raises the importance of tapping into the relevant currencies.

Corporate Culture, in their Human Report, talk about there being seven currencies that motivate people:

- Money

- Time

- Social contact

- Information

- Skills and learning

- Space

- Objects

I’m inclined to believe that there’s an eighth currency, and it’s the currency that nudges often operate under.

The currency of effort.

Having said what I've said, choice architecture is inevitable and unavoidable.

There is always going to be friction that holds us back from making some choices, and lubricant that makes other decisions easier.

And just as information alone is often ineffective, you can’t expect to achieve sustainable behaviour change from people who do not understand why their behaviour needs to change. Nudges help people do the things they already know they should do, and the things they already want to do.

So while it may not always be relevant, effective or appropriate to build a solution around nudging, it will always be of value to design the choice architecture of your solution, keeping in mind the often-overlooked value we attribute to the currency of effort.

Andrew Drummond is a filmmaker, and a behavioural scientist in-training. He’s worked on a range of feature films that have received such accolades as ‘Best Romance’ at the London Film Awards, and ‘Award of Excellence’ at The IndieFEST Film Awards. His interest in and enthusiasm for 'what makes us human' brought him to the University of Stirling, where he is currently enjoying a Behavioural Science for Management MSc. Using his background in film and his passion for people, Andrew works for Corporate Culture where he writes copy, provides videography, and applies behavioural science insights to top-secret proj- I've said too much. There's someone in my house. Send hel...

Seductive Fly artwork credit: Zoe Cheale Instagram @kikichealy